Good tidings and well-wishes!

Like many (if not most) of my fellow blogospheric paleo-nerds, I’ve long been a fan of the cultural sensation that is Ray Troll: the only paleontological (and ichthyological) artist I know of whose work can often be cited as “surreal” (how else would you describe an image like this?). Troll’s eccentric style has, in fact, inspired many of my own doodles over the years. However, another passion of this incomparable illustrator has encouraged me to elect this week’s “spotlight”: namely, his undying adoration for bizarre prehistoric fish.

And frankly, they just don’t get much weirder than the mid-to-late-Devonian lobe-fin Onychodus sp. of Germany, England, Norway, the U.S., the Middle East, the Baltic region, and, most notably, Western Australia.

Although I’m completely certain that the animal’s fantastically bizarre dentition has more than a few visitors to this humble publication thoroughly scratching their heads, this will be discussed in-depth later on (Eh, ain’t I a stinker? 🙂 ).

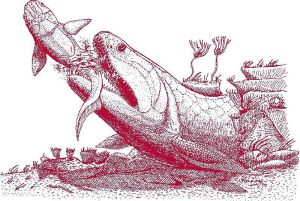

Onychodus is one of the most famous residents of Western Australia’s 375-million-year-old, exquisitely preserved Devonian reef known as the Gogo formation. This paleontologically-vital site has yielded approximately 45 species of fish from essentially every major group alive at the time. As I mentioned earlier, Onychodus itself was an early sarcopterygian or “lobe-fin”, meaning that, in life, its fins were fleshy as opposed to bony and ray-like. More specifically, the (roughly) 2-to-4-meter-long beast is the namesake genus of both the Onychodontida order and Onychodontidae suborder: an exact list of distinguishing characteristics concerning both may be found here.

Onychodus is one of the most famous residents of Western Australia’s 375-million-year-old, exquisitely preserved Devonian reef known as the Gogo formation. This paleontologically-vital site has yielded approximately 45 species of fish from essentially every major group alive at the time. As I mentioned earlier, Onychodus itself was an early sarcopterygian or “lobe-fin”, meaning that, in life, its fins were fleshy as opposed to bony and ray-like. More specifically, the (roughly) 2-to-4-meter-long beast is the namesake genus of both the Onychodontida order and Onychodontidae suborder: an exact list of distinguishing characteristics concerning both may be found here.

Onychodus reconstruction. Note that the animal was much more sinuous and eel-like in life.

In the event that anyone interested in paleo-ichthyology and the field’s Australian front in particular might wish to acquire a source of further information, I’d most heartily recommend John Long’s excellent book on the subject entitled “Swimming In Stone: The Amazing Gogo Fossils Of The Kimberley”, which dedicates an entire chapter to this marvelous fish. In it, Long writes:

“Onychodus [was first described] in 1857 from isolated tooth whorls, which are sets of curved, dagger-like teeth anchored to a thin bony base. These stabbing lower-jaw teeth are the most characteristic feature of Onychodus and have enabled palaeontologists to identify it from Middle-Late Devonian rocks in many parts of the world, including the United States, Germany, the Baltic region, the Middle East, and Australia. But the Gogo material is the only known occurrence of articulated, nearly-complete specimens. The Gogo Onchyodus skulls are so well-preserved that when we close the mouth of a reconstructed skull, the lower jaw teeth [will] actually stab through the top of the skull if they couldn’t retract into the mouth. Just as vipers have elastic ligaments that allow them to move their fangs as they open and close their mouths, so Onychodus must have been able to rotate the huge tooth whorls outwards as its mouth opened, and retract them with closure. The extensive cartilaginous jaw joints also indicate extraordinarily wide jaw movement of 120 degrees or more!”

A reconstructed fragment from an Onychodus tooth whorl.

Onychodus lower jaw reconstruction.

The conclusion that Onychodus predated upon contemporary fish, while decidedly unsurprising, has been graphically supported by a juvenile Gogo specimen of the animal which boasts the remains of a small, unidentified placoderm tucked away in its skull. The latter creature was an estimated 30 cm in length while its attacker is believed to have stretched for approximately 60 cm in life. Ergo, this particular Onychodus likely died as a result of attempting to swallow a victim which was half of its own size: a predicament similar to that which almost certainly befell the participants of the famed Kansan “fish-in-a-fish” skeletal pair.

But just how did Onychodus capture its prey and, more interestingly, how did its distinctive tooth whorl come into play? To answer this most engaging question, I shall once again turn to John Long who writes:

“Onychodus… [has a] retractable tooth [whorl] and a… specialized short braincase structure that allows a high degree of movement. Such features are perfectly in accord with the early specialization of an ambush-lunge predator that crunches down hard on its prey with massive stabbing teeth. Like the modern moray eels, which its skull superficially resembles, I envisage Onychodus lurking within dark crevices in the reef waiting for unsuspecting prey to pass by the opening before it darts out and grabs it, And as its mouth closes, the retractable whorls bring the struggling prey further into its huge mouth and throat cavity. Finally, with a few quick but well-timed lunges forward, the prey is swallowed whole…

[Some 2001] Onychodus material from Gogo revealed some amazing features. The sensory-like canals, which in early lobe-finned fishes are normally confined to the bones surrounding the eye, opened into the upper jaw bone on Onychodus, which would have enabled the hunter to utilize a special sensory field immediately in front of its jaws. The braincase was ossified in the front half; the rear half was largely cartilaginous. This would have been useful as a shock absorber when biting down hard. The pectoral girdle bones, which are usually tightly fitting in many primitive oteichthyans, were usually loose fitting, enabling the fish to open its jaws really wide. All these features spoke to me of one thing: predation.”

While Onychodus‘ cranial morphology is indubitably fascinating, the anatomy of its pectoral fin is far more significant in the evolutionary sense. Prior to the discovery of Panderichthys (and the slightly-younger but much more famous Tiktaalik), Onychodus was in fact the oldest known vertebrate of any kind to sport the basic tetrapod limb pattern of a humerus connected to a radius and ulna for quite some time. This facet of the fish’s anatomy corresponds quite nicely to the hypothesis of it being an ambush predator: such powerful forelimbs, when coupled with its muscular, serpentine post-cranial body, could have easily assisted the beast’s forward lunges while assailing its prey.

May the fossil record continue to enchant us all!

May the fossil record continue to enchant us all!

woo. That’s a pretty fearsome fish. Imagine reeling in you line and finding that on your hook! Why hasn’t this thing appeared in exhibits and tv shows about prehistoric sea monsters? He certainly meets all the criteria!

Also, i wonder how many times this guy has been thought of in discussions of Helicoprion’s tooth whorl. Could the infamous Carboniferous buzzsaw have used it’s teeth in a similar way?

Hey, Doug!

Sorry for the late response. As I understand it, the current paleo-ichthyological consensus regarding Heliocoprion is that its whorl was too rigid to enable the sort of mobility espoused by Onychodus.