Good tidings and well-wishes!

When one takes a glance at the evolution of extant organisms, it is often discovered that many of the most iconic, rare, or recognizable creatures currently inhabiting this planet are but remnants of a once diverse and populous lineage. Living coelocanths are all that remains from a group of fish which was once highly abundant and various, modern horses (of the genus Equus) are the sole survivors of a group which formerly ranged throughout Europe, Asia, and North America, and crocodylians have through their history filled such roles as oceanic predators, greyhound-like hunters, and even herbivores!

A prime example of this may be found in modern proboscideans (elephants and kin). Three fairly-similar species exist today; the Asian elephant (Elephans maximus), the African bush elephant (Loxoconta africana), and the African forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis). But as with all of the aforementioned examples, the group was once far more diverse, including the heavily-muscled Stegomastodon species of the Americas, the Italian Anancus adorned with ridiculously-long tusks, the enormous African Deinotherium equipped with banana-shaped tusks on its lower jaw, as well as everyone’s favorite woolly ice-age inhabitants and kin (though it should be noted that mammoths were a quite diverse group in and of themselves, but this is fodder for a later post).

And then there are the Amebelodontids, which roamed North America, Asia, and Africa during the late Miocene (roughly between 11 and 5 million years ago) and are affectionately-known as ‘shovel-tuskers’:

A replica of Amebelodon, the name-giving species.

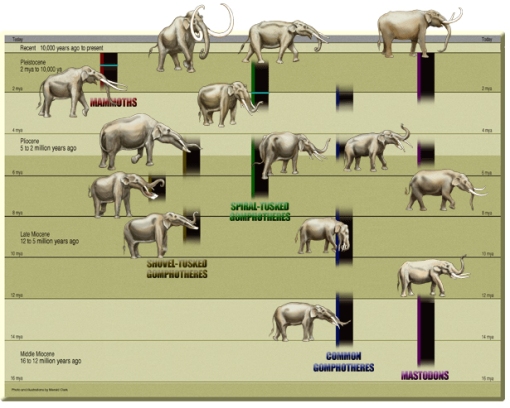

The group is characterized primarily by their distinctive flat lower tusks. The shovel-tuskers belong to a group of proboscideans known as “Gompotheres” which contains two other groups: the basal (or ‘common’) gompotheres which hosted elongated upper and lower tusks and the ‘spiral-tuskers’ which more closely resembled modern elephants in as much that the upper tusks were prominent while the lower ones were either greatly reduced or entirely absent.

As you can see based on this chart, the shovel-tuskers were the least successful members of the gompotheriidae, however they are arguably the most famous and easily the most recognizable. Note, however, that one of the earliest proboscideans, a creature known as Phiomia serridens (pictured below) which lived during the late Eocene to early Oligocene (approximately 36-35 million years ago) of Africa, bore a striking resemblance to Amebelodontids. Despite this, its specific affinities have been disputed as the animal is likely a far more basal proboscidean and thus, for the purposes of this article, will not be included as a member of the group.

Phiomia skull, courtesy of Wikipedia.

The oldest creature definatively-categorized as a shovel-tusker was Archaeobelodon filholi which hailed from the first half of the Miocene in western Europe and Africa. Other genera include Amebelodon (the name-giving species) from North America (and China, to which it probably migrated across the Bering Strait), Platybelodon from the early to late Miocene of Africa and Western/SouthEast Asia, Serbelodon of the Asian/North American Miocene, Eubelodon of the African/European Miocene, as well as Torynobelodon and Gnathabelodon of the North American Great Plains at this time.

Though members of the group are noticably similar, differences between genera are nevertheless present. Within the genus Amebelodon alone, shoulder height amongst species ranged from seven to just over ten feet (2-3 meters). The two most famous genera and the ones which will be most heavily-focused upon by this post, Amebelodon and Platybelodon, can be distinguished from each other by the following features:

1) While the upper tusks of Platybelodon are relatively straight and merely pointed towards the ground in life, those of Amebelodon actually curve downward slightly.

2) The upper jaw of Amebelodon was slightly narrower than that of Platybelodon.

3) The teeth of Amebelodon had comparatively-lower crowns.

4) The symphysis (a fusion between two bones, in this case we’re discussing the “symphysis menti” which fuses the two halves of the lower jaw, anatomically known as the ‘mandibles’) of the Amebelodon species is significantly longer than that of the Platybelodon species.

When one gazes upon the bizzare muzzle of these animals, the inspiration for their nickname becomes obvious. However, upon glancing at the bare skull of a Platybelodon , other oddities become apparent:

Platybelodon skull.

If you find yourself capable of drawing your attention away from the lower jaw, check out the upper tusks. Though I mentioned their orientation before, it’s unusual because while most proboscideans had some sort of upper tusk, in these beasts (unlike nearly all of their relatives) they point down! Interestingly, the original reconstructions for the American Mastodon depicted it’s (considerably larger) upper tusks in such a fashion, however this was done in light of the fact that the first men to take scientific interest in the animal (including many of our founding fathers such as the incomparable Thomas Jefferson) believed it to be a brutish carnivore. For more information on this curious relationship, please visit Paul Semonin’s site.

Despite this, Platybelodon and its relatives do share a certain feature with American mastodons still recognized by some scientists: their teeth. Compare the chompers of the previous picture with those of an American Mastodon:

American Mastodon (Mammut americanum) skull: it's not hard to see why early scientists thought these guys were carnivores!

And of a modern African elephant:

African elephant (Loxodonta sp.) skull. Note the comparatively flatter teeth.

With all this information in mind, the question remains; what were these specializations used for? Before we proceed further, I must confess that while I am a paleo-proboscidean enthusiast, I am by no definition an expert (as of yet). However, various theories have been suggested over the years. The most popular of these has historically been the notion that the spoon-like lower jaw was utilized for ‘raking in’ water plants. At the onset, this makes sense: it would enable the creatures to scoop up this foodstuff en masse with further assistance coming from the trunk.

But there are a few little details which fly in the face of this interpretation. For one thing, have a go at those teeth. Elephants have a tooth-replacement process which is rather unique: while in most animals a new tooth rises up from beneath an older one and eventually displaces it and usurps its function, proboscidean teeth replace each other via conveyor-belt. The front (and thus, older) teeth move forwards in the jaws before they fall out with eccessive wear and are replaced by teeth emerging from behind them. Elephants go through six sets of four teeth (generally with one in each side of the upper and lower jaws, though during the replacement process, two may be briefly present) through the course of their lives (in some recorded instances, ages of 40-60 years have been obtained). The reason for this is likely due to the comparatively-slow growth rate elephants have when compared to other mammals: were a baby elephant to recieve its full-sized adult teeth in its earlier years like many ungulates (“hoofed mammals”), the result would be a death sentence. This process is not without its price, as when an elephant looses its final set of teeth it dies of starvation despite the fact that, according to many experts, they could easily be capable of living longer were it not for this.

How is this relevant to shovel-tuskers? Well, elderly elephants who’ve lost most of their last set of teeth and thus can no longer graze on conventional grassland foodstuff frequently travel to swamps to dine on softer aquatic plants. In other words, animals without particularly powerful dentitions will (for a time) make a living off of swamp plants. Take another look at the teeth of the African elephant and those of Platybelodon and it becomes obvious that the latter is not meant for the job. This is where the similarity to the mastodon teeth comes in, for these were designed to chew up forest-dwelling vegetable matter such as leaves, pollens, mosses, twigs and pine needles (though it should be noted that at least some individuals living in the Great Plains states consumed large amounts of grass), nearly all of which are substantially tougher than water plants and require this type of dentition (however, realize that grass is in turn tougher than almost all of these).

There are more nails to be driven into the aquatic plant diet theory’s coffin, chief among them may be found in the enlarged lower tusks themselves. David Lambert, a reknowned expert on paleo-proboscideans, has noted that some individuals of Amebelodon display extensive scarring in this area. Upon analyzing these wear patterns, he deduced that these were most likely caused by running their tips vertically against the trunk of a tree, thus scraping the bark from its target with some efficiency. The removed sheets could be chewed with relative ease, courtesy of those specialized teeth.

But can an animal make a living off tree bark? Many species of living animals (such as chimpanzees) will turn to this food source during the mid-rainy season wherein fruit becomes scarce, sometimes consuming the various barks of over 21 species of trees and vines during this time. Similarly, porcupines usually depend upon the substance during the harsh winter climates which prevail through most of their range. However, few vertebrates can scratch out their required nourishment exclusively from tree bark, and with a group of animals containing members the size of modern elephants, it’s unlikely that the Amebelodontids were an exception. Though they probably lived off of tree bark for much of their lives (perhaps primarily during the winter), they likely rounded out their diets with other plants as well. Many may have even engaged in the shoveling of water plants described earlier and perhaps put their lower jaws to further use during arid seasons by digging for water with them as well. Mastodons are most commonly depicted as having been “browsers” of various plants (again, this is material for a future post), and I believe that this description suits the shovel-tuskers quite well.

Lambert also noted that most reconstructions (such as the first picture of this post) depict Amebelodon, Platybelodon and kin as possessing a short, stubby, ‘flap-like’ trunk. He suggests that they more likely featured a longer, flexible trunk as seen in modern elephants. This makes sense to me, as the elephant trunk is both incredibly strong (capable of lifting logs) and extremely refined (also capable of picking up individual blades of grass)…such a body-feature would be of great use to any animal boasting it. That said, the trunk was likely modified somewhat, though probably not to the extent of merely becoming a fleshy ‘flap’ as seen in most pictures. I say this because modern elephants rely exclusively on their trunks to bring food into their mouths, but Amebelodontids were capable of using their unique lower jaws to assist them in scooping up food. Therefore, the trunk likely occupied a far less prominent role in obtaining nourishment, and likely was somewhat altered accordingly.

In defense of the illustrations, however, while the length of the trunk therein depicted is likely inaccurate, the width may not be so. Let’s do another comparison, this time with another view of a Platybelodon skull:

Platybelodon skull.

And that of a modern African elephant from a similar angle:

Modern African elephant skull.

Take particular note of the nasal openings. While the one found in the modern elephant is relatively-circular, it’s counterpart in Platybelodon has a bit more of a ‘bulge’ at its center which extends to the base of the hole. Hence, the animal probably had a wider, flatter trunk than its present-day relatives.

Alright then, thus far we’ve discussed the dentition, lower tusks, and trunks of these animals. But what of the downward-pointing upper tusks? These also appear in basal gompotheres such as Gompotherium itself (though in these animals, they’re significantly longer). Within the shovel-tuskers, however, their length and orientation varies somewhat. Here’s a North American species whose identity escapes me at present. (Its probably some species of Amebelodon, though the photographer didn’t mention what exactly it was and erroneously calls it a ‘mastodon’). Compare these tusks to those of the Platybelodon skull above and you’ll see what I mean. So what exactly were these used for? Well, in most species, they compliment the lower tusks quite nicely and together they could have formed a ‘pincer’-like shape, possibly for food gathering. If the bark-eating hypothesis is correct, perhaps they might have also been pressed against tree trunks to help steady the lower jaw while scraping. They may have also been used for combat, however, if this is the case, it’s difficult to imagine how animals with shorter upper tusks would have fought with them without the lower jaw getting in the way. Further research into the logistics of shovel-tusker jaw morphology must be done before we can reach any conclusions on this topic.

To close this worringly-lengthy post, here’s a link highlighting the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s 1995 highway-salvage paleontology dig which unearthed the first Amebelodon skull within the cornhusker state.

Happy tuskin’!

May the fossil record continue to enchant us all.

Hi Mark :

Enjoyed your excellent article on gompotheres.

Did not know that they existed until I went to an exhibit by U.C. Berkeley showing some of their Miocene finds at Blackhawk Quarry. They had about 6 gompothere specimens mounted. As I recall, they stood 6 feet to the shoulder and had ridiculously long tusks going straight out at 11 feet. Could these be like the Italian species? This was some yrs ago, so I hope that my memory is correct.

Since then, I have done a lot of reading on the Miocene Period. Very fascinating.

Turns out, California has some pretty good fossil beds from that period. Blackhawk Quarry is just east of San Francisco and then we have the extensive quarry (20 miles long) just outside of Bakersfield. Unfortunately, we do not have a museum here to showcase these wonderful finds. At Berkeley, the “Museum ” is non existent. All the fossils are in drawers or within steel cases off limits to the public.

Howdy, Bruce. I’m glad that you liked my post!

I believe the Italian species you’re referring to is Anancus sp., which, while a gompothere, lacked tusks on its lower jaws as more primitive forms did (though it certainly had enough tusk to go around, as it’s upper pair extended for over 11 feet).

It’s unfortunate that you are unable to display your apparently exquisite specimens in a museum. Hopefully, Berkely will establish a more comprehensive one in the near future in which to mount some of its many fascinating specimens.

Excellent post! I will now add this blog to my list.

Yeah, we have some great fossil sites out here in CA: Barstow, Avila Beach, Blackhawk Ranch, Anza Borrego, Sharktooth Hill, and loads more.

Tis a shame about Berkeley, I know. They claim to have the largest collection of fossils for a university in the world, but they don’t do anything with them other than research (it irks me that they call themselves a museum. In my eye, they are an institute). They have a small public display, the Lawrence Hall of Science, but far as i can tell (i haven’t actually been, but I’m hoping to when i go up that way in the spring) all they have is that cast of Gomphotherium from Blackhawk : http://www.flickr.com/photos/27363445@N06/3445051083/

With all the stuff they have, based on what they talk about on their website, they could put on one hell of a museum: the original La Brea material, Pleistocene mammals from Australia, a partial Rhynchotherium from Kern County, a fossil whale fall, and much more. Shame that they just sit around, as Bruce noted, in cabinets and drawers, where they get to come out once a year during open house for people to see.